The electric vehicle renaissance is here, but don't take Elon Musk's word for it. In the first few weeks of 2022, legacy automakers and newcomers alike have made commitments to rolling out or ramping up their versions of a battery-powered car within the year.

Earlier this month, Ford announced that it was doubling production of its all-electric F-150 Lightning to 150,000 vehicles per year due to high demand. GM then followed this up by unveiling its new electric version of the Chevrolet Silverado pickup truck. Sony, meanwhile, presented its concept for an electric car at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

These are just a few stand-outs. The 2022 line-up includes new models from Cadillac, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and Hyundai, as well as electric-first companies such as Lucid and Rivian. In other words, the days of Tesla generating the lion's share of EV buzz are over.

Industry projections back up what looks like a major leap forward for EV adoption. Global sales in the space were on track to hit 5.6 million in 2021, according to a report from BloombergNEF prepared for COP26. That's up from 2.1 million in 2019, with EVs now making up 7 percent of the auto market. Bloomberg NEF projects that annual sales will double again in 2022 to 10.5 million.

For those tracking EVs' decades-long rise from pipe dream to cars in the pipeline, this is the moment many have been waiting for: a mass market for battery-powered cars. Success comes with tradeoffs, however, and one that is emerging as arguably the biggest challenge to the rise of electric vehicles is their outsized demand for rare earth minerals.

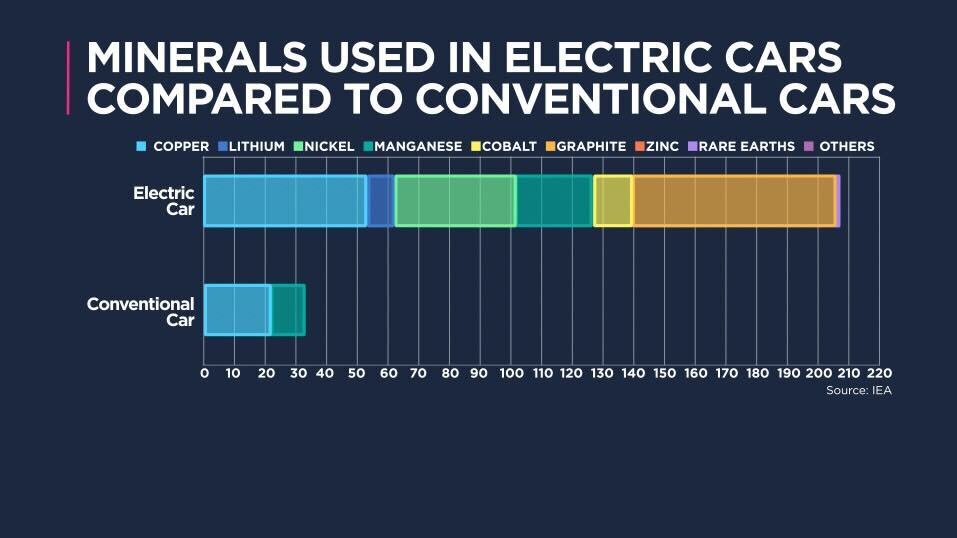

Electric vehicles require six times the amount of minerals of conventional cars. That includes minerals commonly used in all cars, such as copper and manganese, but also some that are specific to lithium-ion battery production, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite. As production ramps up, the supply of these minerals has to keep pace with demand for automakers to meet their EV targets, and increasingly suppliers are feeling the strain.

“Today, the data shows a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realizing those ambitions,” said Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), in a report highlighting the critical role of minerals in making the transition to electric vehicles possible.

The agency predicts that the EV market could require anywhere from six to 30 times the current supply of key minerals, such as cobalt and lithium, to meet industry needs. Based on current levels of investment worldwide, the output isn't likely to match that demand, according to IEA.

Making matters worse, mining operations for rare earth minerals are highly concentrated in a handful of countries. The lack of diversity introduces a number of geopolitical concerns, as countries and corporations vie for resources to meet their respective climate agendas.

"One of the common characteristics of these rare metal supply chains is that a lot of them are extremely vertically integrated and dominated by one entity, usually China," Everett Millman, a precious metal specialist at Gainesville Coins, LLC, told Cheddar.

Already, the prices of key minerals are skyrocketing. Lithium was up as high as 500 percent year-over-year this week, and cobalt and nickel were up as high as 80 percent and 33 percent respectively. While battery costs have been dropping for years due to economies of scale, minerals now make up a larger chunk — about 30 percent — and battery prices are rising with them.

"Battery pack costs have increased and battery makers have made public announcements that prices will increase," said Scott Yarham, metals expert at S&P Global Platts. "This is very unusual for battery costs which have consistently been moving down for years."

He added the market is likely to move into deficit unless major investments are made.

This leaves electric car companies at the mercy of a global supply chain that could be unprepared to meet their long-term needs, and given that EVs are at the center of global efforts to tackle climate change, tight supply could hurt more than automakers' bottom lines.

It could also throw into doubt one of the pillars of the green transition.

Mad Dash for Minerals

Not all EV companies will be taken by surprise though. Many have been bracing for this situation for some time, and are scrambling to secure their own supplies.

Tesla, predictably, was well ahead of the curve in this area. The company has struck a number of direct partnerships with miners, rather than working through battery suppliers. Just this month, for instance, Tesla struck deals with Talon Metals for a U.S.-based supply of nickel and with Australia-based Syrah Resources for a line on graphite sourced from Mozambique. Tesla framed both deals as a way to diversify its supply chain outside of China.

Legacy automakers are following suit by getting more involved in the production of EV batteries. Ford last year announced plans to build two battery plants in Kentucky and one in Tennessee, in partnership with South Korean battery cell supplier SK Innovation. This isn't the same as partnering directly with miners, but it places Ford right in the middle of the battery business.

Jeep-maker Stellantis, which is headquartered in Amsterdam, recently struck a deal with Vulcan Energy Resources to secure battery-grade lithium hydroxide from Germany — another case of a company trying to work with suppliers closer to home.

All of this is highly unorthodox for the global commodities market and works against decades of precedent when it comes to automobile supply chains.

"It's never been successfully done before if you look back in history when consumers try to get involved in the material end of the business," said Lewis Black, CEO of Almonty Industries, a tungsten mining operation that supplies battery manufacturers.

He noted that commodity trading houses have a purpose, which is to shield companies like Ford and GM from "all the nonsense that goes on in raw material supply."

Now car manufacturers are willingly getting involved in the mining business, which itself is under the radar for its track record of labor abuses and heavy environmental impact.

But companies are in a bind. If the demand coming down the pike significantly outpaces supply, a zero-sum battle for resources could winnow the field of EV companies.

"I understand why," said Black. "It's going to be a race for raw materials. If you can't secure the raw materials, you're going to get left behind by those who do. Any car manufacturers that have access to the entirety of the supply chain will win the market share."

This kind of zero-sum approach to materials sourcing could also apply to nations. Indonesia, the largest producer of nickel in the world, recently rattled global markets when it cut off exports of certain minerals to encourage more value-added processing at home.

Chris Vecchio, senior analyst for DailyFX, said the lack of government support for the electric vehicles industry in countries like the U.S. only makes the situation more cutthroat.

"Unless you have the backing of a state enterprise to ensure you have the financial and geopolitical weight to throw around to gain access to cobalt mines or nickel mines, it's going to be increasingly difficult for new players to enter the space," he said.

This recalls what happened to some U.S.-based electric vehicle pioneers nearly a decade ago, when a lack of government support and competition from the existing automakers led to firms such as Fisker Automotive going bankrupt and being purchased by Chinese companies.

Vecchio said he expects a wave of mergers and acquisitions activity in the EV space over the next decade, as smaller companies get eaten up by larger, better-supplied players.

Tough Sell

The obvious answer to the threat of supply shortages, according to many industry-watchers, is a massive round of investment in new mining capacity.

While this is beginning to happen for certain minerals, it's unclear if the current level of investment will be enough, particularly in the short term. Take the case of lithium.

"More investment was made in 2021 than the last three years combined, but these projects take time to come online," Yarham said. "It's not like a tap you can just switch on and there's battery-grade lithium."

He explained that lithium prices were in the doldrums through much of the 2010s, including up to 2019, which left many investors "severely burnt" and hesitant to re-enter the market.

Accounting for both existing mines and projects under construction, the IEA said the expected supply is estimated to meet just half of projected lithium and cobalt requirements by 2030.

Other minerals such as cobalt had a similar trajectory in recent years, but lithium is the most strained. Nickel, for its part, is in a unique position, because demand is not dominated by the battery market. Most nickel still goes to stainless steel production.

Market logic would suggest that growing demand and higher prices will eventually fuel a commodity supercycle like the one that drove up commodity prices throughout the 2000s, ultimately driving up investment and global supply.

But things have changed since the last supercycle, said Black of Almonty Industries, which has tungsten mines in Spain, Portugal, and South Korea.

He points to the emergence of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) standards as the biggest challenge. "ESG is the holy grail of all miners. You must comply with ESG," he said.

This means countries with more lax regulatory standards like the Democratic Republic of Congo — which exports the bulk of cobalt globally — could become less viable for investment.

At the same time, countries with higher standards present their own challenges. Many countries with robust environmental movements often face fierce resistance to new mining projects.

Notably, there is just one lithium mine in the U.S., and efforts to develop other deposits have come up against resistance from local communities.

Vecchio said the situation highlights how the broader push for electrification — whether you're talking about automobiles or energy generation — comes with some serious costs, which may be difficult to swallow for environmentalists and others wary of the mining business.

"This is one of those trade-offs that environmentalists need to wrap their heads around," he said. "If the long-term goal for switching to EVs is to decrease pollution and ward off the most devastating effects of climate change, then there's going to be a short-term cost that's incurred, and that paradoxically might be more environmental degradation."

More regulations and public scrutiny also mean more time to get a project up and running, and with nations setting deadlines for a green transition, the timeline for the EV rollout is crucial.

"To open a mine in a safe jurisdiction takes years — years in the applications, the permits, the design work, the financing, the construction, and the commissioning," Black said. "Soup to nuts, it's eight to 10 years, because regulations are very stringent, as they should be."

Black commended President Joe Biden for an executive order early in his administration calling for a diversification of the EV supply chain but said it has so far brought few tangible benefits.

The bipartisan infrastructure package did include nearly $7 billion in funds for various programs related to expanding battery production in the U.S. Most of these are devoted to research and offer little relief to automakers in the near term. But scientific advancement could shift the market, as new battery technology using fewer or different rare earth minerals is a possibility.

In the meantime, China continues to dominate the EV industry by working directly with both automakers and battery suppliers to help them secure the materials they need.

"If you want to open a mine in China, and the state wants you to open it, it's open," Black said.