By Robert Jablon

David Crosby, the brash rock musician who evolved from a baby-faced harmony singer with the Byrds to a mustachioed hippie superstar and an ongoing troubadour in Crosby, Stills, Nash & (sometimes) Young, has died at 81, several media outlets reported Thursday.

The New York Times reported, based on a text message from Crosby's sister in law, that the musician died Wednesday night. Several media outlets reported Crosby's death citing anonymous sources; The Associated Press was unable to reach Crosby's representatives and his widow.

Crosby underwent a liver transplant in 1994 after decades of drug use and survived diabetes, hepatitis C and heart surgery in his 70s.

While he only wrote a handful of widely known songs, the witty and ever opinionated Crosby was on the front lines of the cultural revolution of the ’60s and ’70s — whether triumphing with Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young on stage at Woodstock, testifying on behalf of a hirsute generation in his anthem “Almost Cut My Hair” or mourning the assassination of Robert Kennedy in “Long Time Gone.”

He was a founder and focus of the Los Angeles rock music community from which such performers as the Eagles and Jackson Browne later emerged. He was a twinkly-eyed hippie patriarch, the inspiration for Dennis Hopper’s long-haired stoner in “Easy Rider.” He advocated for peace, but was an unrepentant loudmouth who practiced personal warfare and acknowledged that many of the musicians he worked with no longer spoke to him.

“Crosby was a colorful and unpredictable character, wore a Mandrake the Magician cape, didn’t get along with too many people and had a beautiful voice — an architect of harmony,” Bob Dylan wrote in his 2004 memoir, “Chronicles: Volume One.”

Crosby's drug use left him bloated, broke and alienated. He kicked the addiction in 1985 and 1986 during a year’s prison stretch in Texas on drug and weapons charges. The conviction eventually was overturned.

“I’ve always said that I picked up the guitar as a shortcut to sex and after my first joint I was sure that if everyone smoked dope there’d be an end to war,” Crosby said in his 1988 autobiography, “Long Time Gone,” co-written with Carl Gottlieb. “I was right about the sex. I was wrong when it came to drugs.”

He lived years longer than even he expected and in his 70s enjoyed a creative renaissance, issuing several solo albums while collaborating with others including his son James Raymond, who became a favorite songwriting partner.

“Most guys my age would have done a covers record or duets on old material,” he told Rolling Stone in 2013, shortly before “Croz” was released. “This won’t be a huge hit. It’ll probably sell nineteen copies. I don’t think kids are gonna dig it, but I’m not making it for them. I’m making it for me. I have this stuff that I need to get off my chest.”

In 2019, Crosby was featured in the documentary “David Crosby: Remember My Name,” produced by Cameron Crowe.

While his solo career thrived, his seemingly lifetime bond with Nash dissolved. Crosby was angered by Nash’s 2013 memoir “Wild Tales” (whiny and dishonest, he called it) and relations between the two spilled into an ugly public feud, with Nash and Crosby agreeing on one thing: Crosby, Stills and Nash was finished. Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president did lead Crosby to suggest that he was open to a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young protest tour, but his old bandmates declined to respond.

Crosby became a star in the mid-1960s with the seminal folk-rock group The Byrds, known for such hits as “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and “Mr. Tambourine Man.” Clean-cut and baby-faced at the time, he contributed harmonies that were a key part of the band’s innovative blend of The Beatles and Dylan. Crosby was among the first American stars to become close to The Beatles, and helped introduce George Harrison to Eastern music.

Troubled relations with bandmates pushed Crosby out of The Byrds and into a new group. Crosby, Stills and Nash's first meeting is part of rock folklore: Stills and Crosby were at Joni Mitchell’s house in 1968 (Stills would contend they were at Mama Cass'), working on the ballad “You Don’t Have to Cry,” when Nash suggested they start over again. Nash’s high harmony added a magical layer to Stills' rough bottom and Crosby’s mellow middle and a supergroup was born.

Their eponymous debut album was an instant success that helped redefine commercial music. The songs were longer and more personal than their individual prior outputs, yet easily relatable for an audience also embracing a more open lifestyle.

Their spirited harmonies and themes of peace and love became emblematic of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Their version of the Mitchell song “Woodstock” was the theme for the documentary about the 1969 rock concert during which the group made only its second live appearance together. Crosby had produced Mitchell’s first album, “Song to a Seagull,” in 1968, and for a time was her boyfriend (as was Nash).

Now wearing the drooping, bushy mustache that would define him ever after, Crosby provided harmony and rhythm guitar, and his songs reflected his own volatile personality. They ranged from the misty-eyed romanticism of “Guinevere,” to the spirituality of “Deja Vu,” to the operatic paranoia of “Almost Cut My Hair.”

Some critics panned the group as soft-headed and self-indulgent.

“If you’re into living-room rock, fireplace harmonies and just a taste of good old social consciousness, this is your group,” reported Rolling Stone, which nonetheless rarely missed a chance to write about the band.

But CSN, as they would soon be called, won a best new artist Grammy and remained a worldwide touring act and brand name decades later.

The first album was an easy, happy recording, but the mood darkened during the second album, “Deja Vu.” The band was joined by Neil Young, who had feuded with Stills while both were in Buffalo Springfield and continued to do so.

Everyone in the band was troubled: Nash and Mitchell were splitting up, and so were Stills and singer Judy Collins. Crosby, meanwhile, was so devastated by the death of girlfriend Christine Hinton in a car accident, that he would lay on the studio floor and sob.

Featuring a rougher, less unified sound, the album released in 1970 and was another commercial smash. Yet within two years, the quartet had broken up, destined to continuously reunite and splinter for the rest of their lives.

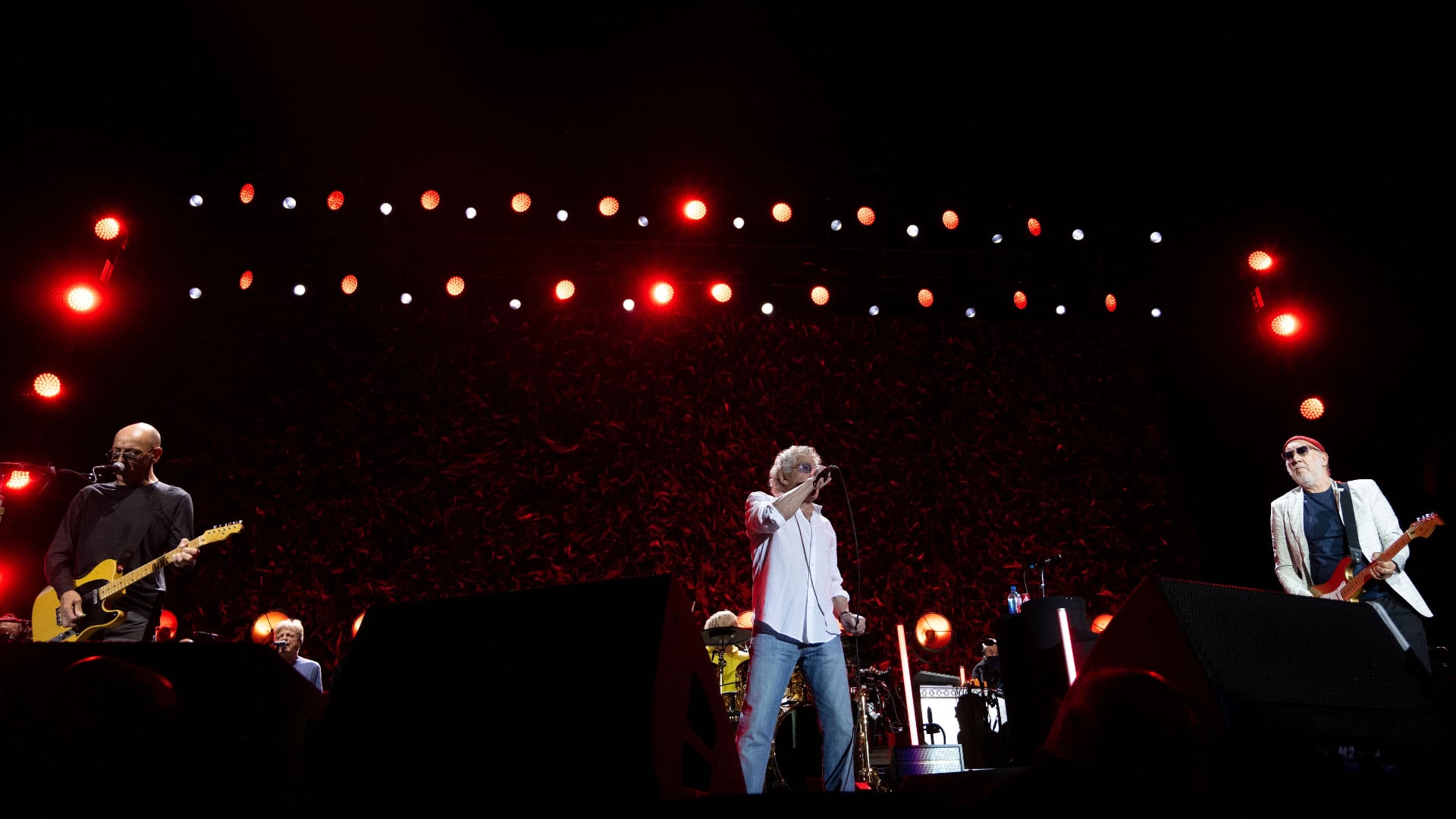

They worked in every combination possible — as solo artists, as duos, trios and, occasionally, all four together. They played stadiums and clubs. They showed up at the Berlin Wall in 1989as the Cold War was ending and turned up in 2011 for the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York.

In recent years, Crosby toured often, and candidly answered questions on Twitter with a blend of affection and exasperation, whether commenting on rock star peers or assessing the quality of a fan’s marijuana joint. He loved sailing and his greatest regret, besides hard drugs, was selling his 74-foot boat because of money problems. Among the songs completed on the boat was the classic “Wooden Ships,” co-written with Stills and Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner.

Crosby was born David Van Cortlandt Crosby on Aug. 14, 1941, in Los Angeles. His father was Oscar-winning cinematographer Floyd Crosby of “High Noon” fame. The family, including his mother, Aliph, and brother, Floyd Jr., later moved to Santa Barbara.

Crosby was exposed early to classical, folk and jazz music. In his autobiography, Crosby said that as a child he used to harmonize as his mother sang, his father played mandolin and his brother played guitar.

“When rock ‘n’ roll came in during that era and the Age of Elvis possessed America, I wasn’t into it,” he recalled.

His brother taught him to play guitar and, still in his teens, he began performing in Santa Barbara clubs. He moved to Los Angeles to study acting in 1960 but abandoned the idea and became a folk singer, working around the country before joining The Byrds. Like so many folk performers, Crosby was dazzled by the Beatles’ 1964 movie “A Hard Day’s Night” and decided to become a rock star.

Crosby married longtime girlfriend Jan Dance in 1987. The couple had a son, Django, in 1995. Crosby also had a daughter, Donovan, with Debbie Donovan. Shortly after he underwent the liver transplant, Crosby was reunited with Raymond, who had been placed for adoption in 1961. Raymond, Crosby and Jeff Pevar later performed together in a group called CPR.

“I regretted losing him many times,” Crosby told the AP of Raymond in 1998. “I was too immature to parent anybody, and too irresponsible.”

In 2000, Melissa Etheridge revealed that Crosby was the father of the two children she shared with then-partner Julie Cypher. Cypher carried the children Crosby fathered by artificial insemination, Etheridge told Rolling Stone. One son, Beckett, died in 2020.

Crosby didn’t help raise the children but said, “If, you know, in due time, at a distance, they’re proud of who their genetic dad is, that’s great.”

AP National Writer Hillel Italie contributed reporting from New York.